The Last Telephone Operator: 1955-1960

by Nancy Brown Tomlin

Suzie Heter, our next-door neighbor, was working nights at the telephone office, and she taught me how to operate the switchboard when I visited her there at night. In Sept 1955, I was hired as an operator, and for a while, the two of us worked the night shift together.

The company we worked for, Gem State Telephone Co., was at that time one of the seven remaining independent (not owned by Bell System) phone companies in the country.

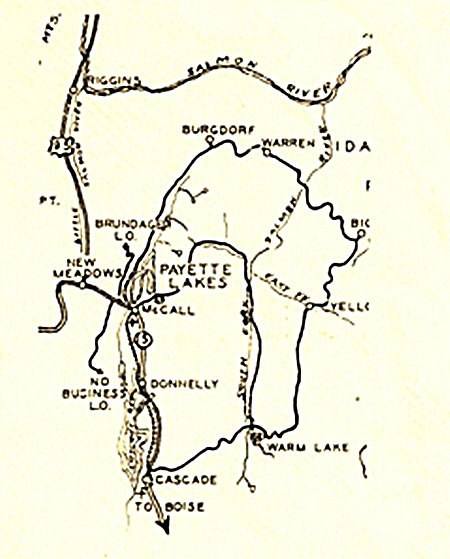

McCall was what was called a "toll center", that is, we were the communications hub for Donnelly, New Meadows, Cascade and Riggins, which were called 'ring-downs'. You couldn't call any of them without going through a McCall operator, just as you couldn't call any other place from McCall without going through a Boise operator. Bell Telephone owned all the 'long lines - all the lines outside our area.

We had one long-distance circuit to each of the local area towns. The New Meadows and Riggins switchboards were in their phone operator's houses. We had to call the operators there and have them ring the local number.

Donnelly and Cascade had dial phones (dialed by the McCall operator) but in McCall we still had 10-party phone lines.

We had three circuits to Boise, and one circuit each for the Forest Service and the Shore Lodge, both of which had their own internal switchboards.

At McCall, we had a 3-position switchboard (room for 3 operators at a time, each sitting in front of a panel that looked just the one Lily Tomlin used in her Ernestine sketches). All the local lines and all the long distance circuits were available at each position.

On the upright part of each position, each line number had a signal light and a hole beneath the light for the jack. The flat part in front of each operator had two rows (about twenty pairs) of flexible cords with jacks on the ends, and there were two toggle switches and two lights in front of each pair of cords. Jacks weren't little plastic doodads; they were metal, and about 3 inches long.

When a phone in McCall was picked up, or someone called in on one of the long-distance circuits, its signal light would come on the upright part of the board, the first operator to reach it would plug the jack of the back cord of a pair of cords into the hole beneath the light, and would push the front toggle switch of the pair backward to talk to the caller. Given the number the caller wanted, the operator would plug the jack of the front cord of the pair into the hole for the called number's line, and push or pull the rear toggle switch the required number of times.

Our home phone number at the time was 39R3. To call our house, an operator would plug into the '39' hole and push the rear toggle switch backward 3 times. For 39W3, she would push the toggle switch forward three times, and so on. On the party lines, of course, everyone on the line could hear the ring, and knew which house was being called by the number of times their phone rang.

Telephone lines have two sides - a 'tip' side and a 'ring' side, that's how Call Waiting works. It allows you to switch from one side of the line to the other. It's also how there could be numbers such as 39R3 and 39W3.

When the jack was plugged in, the signal light on the upright part of the board went out, and the rear signal light in front of the cord pair came on. When the called party answered, the front light in front of the cord pair came on. Operators watched the lights in front of the cord pairs, and pulled out the jacks when both lights went off.

If I recall correctly, when people were connected to either the Forest Service office or the Shore Lodge, there were no signal lights to let the operator know when the callers disconnected, and we had to monitor those lines to see when the call was completed. This was really a nuisance, because if the outgoing calls were long distance, we had to time-stamp a paper ticket at the start and end of each call, and it was really easy to forget to monitor and catch the call as it ended.

As I mentioned, we had 3 circuits to Boise. Even Boise only had a few direct circuits beyond its local area - one to New York City, I think one to Chicago, and maybe one or two other places. So you could only call direct from Boise to a few very places. As a result, long-distance calling was sometimes an adventure for the operator. For calls to any place outside Boise’s direct calling area, we usually had to look up the route in big 'route books' that told you what path to take - sort of like a AAA point-to-point map..

For example, to call Sandpoint, Idaho, the route was: Boise, Pocatello, Deer Lodge (Montana), Butte, Billings, Dubois, Sandpoint. At each station, you would ask for the next one, and then you had to fend off intermediate operators all along the way, as they would periodically check the line and ask if you were through. You had to remember the routing sequence, so you could respond "Holding for Pocatello" or whatever the next town was that you were waiting for a response from.

Operators all developed a sort of sing-song way of saying "Mackall, are you through? Are you through?" You always had to announce your station (town) so the originating operator knew where she had gotten to.

When I first started working for the phone company, we said "Number, please" when answering. This is hard to say quickly hour after hour, so we sometimes said "Lumber knees". Later we changed to answering "Operator" which was easier.

Daytime work in the summertime was sheer hell. It was hot and airless in the office, there were thousands of summer people wanting to call Boise or elsewhere. There were always people at the window by the switchboard wanting something, and the circuits were constantly busy. I believe the only pay phone in town was in our office, so in the summer there would be long lines of people waiting to use it.

During the summer and on major holidays, we just wrote out long-distance tickets as fast we as could take the information and piled them up in order, then made each call as circuits became available. When it was really busy, we designated one operator as "Long-distance" and all she did all day was write tickets and try to place calls. It sometimes took days to get a call through.

The pay phone and Shore Lodge were really the pits when you were busy, as you had to figure the time and charges for the caller as soon as the call was completed.

In those days, you could really get personal service. If someone was looking for a friend who was staying in a hotel somewhere but they didn't know which one, you could issue a "Ticket Locate" and a local operator would call every hotel or motel in their area looking your party.

If you didn't know the name of a business you wanted to call, the operator in that town would usually make suggestions of places to try, and would even call 3 or 4 places for you - even in places like Los Angeles or New York. Most places had messenger services for people without phones, and the local police would generally go find your party in case of an emergency.

On a long-distance call, if the number you called was busy, the operator would keep trying it until she got through, and then she would call you back. If the call was person-to-person, and the party you wanted wasn't there, the operator would leave a 'special operator' number for them to call when they were available.

In places the size of McCall, you could call the operator to see if your kid or spouse had tried to call home while you were out.

Winter storms frequently knocked out the power lines, including power to the switchboard. When this happened, we had a back-up battery that kept the emergency lights on, but which didn't have enough power to make the phones ring. Then we would get our little cranks that fit into a hole in the front of each switchboard position and ring the numbers by turning the crank.

One night when I was at work alone, someone crashed into a power pole about 1:00 AM and knocked out the power to everything, including our office. It was pitch dark inside and out. Since the office was normally attended 24 hours a day, there were no keys. I finally had to leave the building unlocked and unattended while I went to the Yacht Club and got the night clerk to go get my boss and the power company supervisor out of bed. None of us were happy.

Working at night was really kind of fun. About 3:00 every morning, the Boise 'toll-test' board would call us to check out the circuits. We always had a good chat with the guys on the toll-test board.

The night cops always dropped in and had coffee two or three times a night in between patrols. The only way to reach them if they were out in their cars was for the operator to turn on a signal light that was on a tall pole on top of the phone office building. The operator also had charge of the town fire siren.

Grid Rowles, my boss, used to talk to me about something called 'area codes' that Bell System was planning on implementing. It seemed pretty far-fetched at the time.

In 1960, the new phone office was built right next door. I was the last operator on the old switchboard the night the cutover to the new dial system was made that November. The cutover was started about 10:00 PM, and all night long, lights flashed randomly on the switchboard as the wires were changed. At about 2:00 AM, the entire switchboard lit up and then died.

|

|

|

Copyright © 2009 - Sharon McConnel. All Rights Reserved.